Fantasy and science fiction were still in their infancy when Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Under the Moons of Mars made its début as a serial in the pages of All-Story magazine in February 1912, less than a year before Burroughs’ more famous creation, Tarzan, made his first appearance. The planet Mars, named after the Roman god of war, had already appeared in a science fiction novel as progenitor of the extraterrestrial aggressors in H. G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds, published in 1898. Yet little was known about the putative ‘red planet’, so called for its reddish hue when viewed from Earth, although the canal-like lesions on its surface led to speculation that it might contain water and therefore life. Thus, Burroughs had a virtually blank canvas on which to paint tales of heroic deeds, hairsbreadth escapes and bloody battles set in the strange and alien landscape where John Carter, a Virginian-born veteran of the American Civil War, finds himself after dying and being mysteriously reborn, apparently through some form of astral projection. On Mars, which the natives call ‘Barsoom’, Carter discovers that the weaker gravity gives him superhuman strength, and he accepts his destiny as a warrior-cum-saviour, protecting the indigenous humanoids from a wide variety of alien life, many resembling the creatures of ancient myth. In the first serialized story, Under the Moons of Mars, Carter wins the hand of a Martian (or Barsoomian) princess, Dejah Thoris of Helium; thus, when the story was collected in novel form in 1917, it was re-titled A Princess of Mars.

Fantasy and science fiction were still in their infancy when Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Under the Moons of Mars made its début as a serial in the pages of All-Story magazine in February 1912, less than a year before Burroughs’ more famous creation, Tarzan, made his first appearance. The planet Mars, named after the Roman god of war, had already appeared in a science fiction novel as progenitor of the extraterrestrial aggressors in H. G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds, published in 1898. Yet little was known about the putative ‘red planet’, so called for its reddish hue when viewed from Earth, although the canal-like lesions on its surface led to speculation that it might contain water and therefore life. Thus, Burroughs had a virtually blank canvas on which to paint tales of heroic deeds, hairsbreadth escapes and bloody battles set in the strange and alien landscape where John Carter, a Virginian-born veteran of the American Civil War, finds himself after dying and being mysteriously reborn, apparently through some form of astral projection. On Mars, which the natives call ‘Barsoom’, Carter discovers that the weaker gravity gives him superhuman strength, and he accepts his destiny as a warrior-cum-saviour, protecting the indigenous humanoids from a wide variety of alien life, many resembling the creatures of ancient myth. In the first serialized story, Under the Moons of Mars, Carter wins the hand of a Martian (or Barsoomian) princess, Dejah Thoris of Helium; thus, when the story was collected in novel form in 1917, it was re-titled A Princess of Mars.

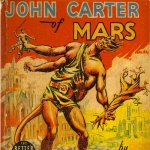

Although the extraordinary success of Tarzan eclipsed other works by the prolific Burroughs, he returned to the red planet to describe John Carter’s further adventures, notably in The Gods of Mars (1918), The Warlord of Mars (1919), Thuvia, Maid of Mars (1920), Swords of Mars (1936), Synthetic Men of Mars (1940), Llana of Gathol (1948) and the eponymous John Carter of Mars (1964), published fourteen years after Burroughs’ death. These works, together with three others, The Chessmen of Mars (1922), A Fighting Man of Mars (1931) and The Master Mind of Mars (1931), have retained their popularity in the years since their publication — so much so that, just as the town of Tarzana, California, had been named after Burroughs’ ranch, one of the largest craters on Mars was named Burroughs in honour of the man who, for generations of fantasy fiction readers, put Mars on the map.

Almost uniquely for his time, Burroughs was adroit at capitalizing on the success of his stories, licensing Tarzan for a number of media, including comic strips, films and merchandise. The author undoubtedly saw similar potential in the character popularly known as ‘John Carter of Mars’, and as early as 1931, animation legend Robert Clampett — creator of Porky Pig and director of many memorable Looney Tunes cartoons — approached Burroughs with the idea of turning A Princess of Mars into the first feature-length animated film. Burroughs was enthusiastic about the project, compiling an extensive array of sketches, sculptures and production notes with the help of his son, Tarzan and John Carter cover artist John Coleman Burroughs, ultimately convincing Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer to pick up the rights to the stories, with a view to releasing the film as early as 1932. Burroughs, Clampett and the studio did not share a common vision for the project, however; MGM’s desire to make a slapstick comedy with a swashbuckling hero was in sharp contrast to Burroughs’ hope for a serious sci-fi spectacle more in keeping with the tone of the stories. After a year of development, the studio pulled the plug on the project, leaving Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs to become the first feature-length animated film five years later.

Despite a passing interest in the late fifties from stop-motion animator Ray Harryhausen, several decades passed before John Carter of Mars was seriously considered as the subject of a motion picture once more, this time as a live action Disney feature which, the studio hoped, would capitalize on the success of such ‘sword-and–sandal’ epics as Conan the Barbarian along with the post-Star Wars taste for science fiction. Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio, who would later write Aladdin and Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl for Disney, Godzilla and Shrek, were hired to write the screenplay, while Mario Kassar and Andrew G. Vajna, producers of the Rambo films and partners in the Carolco financing and production venture which would later produce Basic Instinct and Terminator 2: Judgment Day, were brought aboard as producers. They, in turn, courted Die Hard director John McTiernan and Hollywood top gun Tom Cruise. But the sheer scale of the endeavour, coupled with what McTiernan saw as the limitations of special effects, led to the project’s eventual collapse. Disney retained the rights to the stories throughout the following decade, with Jeffrey Katzenberg an enthusiastic proponent of the project, but the 1990s were not kind to live action fantasy stories, and the studio eventually put the project in turnaround, making the rights available once more.

The success of the first film in Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy in 2001 made fantasy seem like a viable box office proposition once again. Like gambling addicts trying to bet on a race which had already been won, every studio began scouring its rights department in the hopes that it held the option on another epic fantasy; in the space of a year, big budget films based on The Chronicles of Narnia, His Dark Materials, Eragon and The Spiderwick Chronicles were all in various stages of development and/or pre-production. When the dust from this epic scramble cleared, the rights to the John Carter of Mars stories were still, miraculously, available. If The Lord of the Rings and George Lucas’s Star Wars prequels had struck box office gold in the new millennium, could the combination of science fiction and fantasy in a single film spell alchemy?

Harry Knowles, founder and webmaster of the influential film gossip web site Ain’t It Cool News, had always thought so. A lifelong Burroughs fan and long-time advocate of a film adaptation of the Barsoom stories, in July 2001, in his afterword to the first edition of this book, Knowles described John Carter of Mars as “the greatest sci-fi film that never was”. A year later, Knowles waxed lyrical about the stories in his autobiography, Ain’t It Cool? Hollywood’s Redheaded Stepchild Speaks Out, and this time, someone at the sharp end of the movie-making machine was paying attention: producer James Jacks, who, with partner Sean Daniel, had produced the hit re-imagining of Universal’s The Mummy and its smash hit sequel, The Mummy Returns. Jacks, who had read Carter’s adventures as a child, was reminded of them by Knowles’ book, and convinced Paramount Pictures to acquire the rights on behalf of his and Daniel’s production entity, Alphaville Productions. As soon as the rights had been secured — for $300,000 against $2 million, following a bidding war with Columbia — Jacks paid his debt to Knowles, bringing him aboard as an unofficial advisor on the project, while Mark Protosevich, who scripted The Cell (2000), worked on the screenplay.

Once the script was completed, most producers would begin sending it out to talent agencies, looking for a director. However, with a project so dear to his heart, Knowles preferred to leave nothing to chance. As a resident of Austin, Texas, Knowles knew a local filmmaker who he thought would be perfect to helm the $100 million-plus project. But Knowles’ friend was no film school buddy: it was Robert Rodriguez, maverick director of From Dusk Till Dawn and the Spy Kids trilogy. Knowles passed the script to Rodriguez in late 2003, and by the end of the year Rodriguez had come aboard as director and agreed to serve as a producer, along with his wife Elizabeth Avellan, partner in his production company Troublemaker Studios. Speaking to Variety as his involvement was officially announced, Rodriguez said that he hoped to begin shooting the film, which might be titled A Princess of Mars or John Carter of Mars, in early 2005. “After Lord of the Rings, this is probably the last well known fantasy classic yet to be made, and that’s because it wasn’t possible until technology caught up.” In the same article, Jacks described the project as “one of the great fantasy/adventure stories of all time,” but admitted that it was challenging because the Star Wars prequels and Lord of the Rings films had set the bar so high. Nevertheless, the producer credited Protosevich, who had recently adapted Richard Matheson’s fifty-year-old story I Am Legend, for excising the “creaky” aspects of the ninety-year-old novel.

By April 2004, Knowles himself was invited aboard in an official capacity: as producer number five. “So many filmmakers go to him for advice and he does it under the table,” Rodriguez told Hollywood Reporter. “I’ve always said to him that he should get credit for this, and with all the work we’ve done on this project, he deserves it.” Jacks agreed. “He was very instrumental in us landing Robert, and he is truly well versed in all the John Carter books. With the help he had given and the help that he will give, it seemed only right that we include him in the movie, so we asked him to be a producer.”

Rodriguez’s attachment meant that John Carter of Mars would be shot using his preferred format: high definition progressive scan digital cameras on digital film, a process he continued to perfect during his work on Sin City. It was Rodriguez’s decision to co-direct that film with its creator, Frank Miller, and include his friend Quentin Tarantino as ‘special guest director’, that led him to resign from the Director’s Guild of America (DGA) in March 2004, in protest over the union’s refusal to allow more than one director to be credited on a film, unless they are a “bona fide co-directing team,” as in the case of the Coen or Wachowski brothers, or co-directors of an animated feature. Since Paramount Pictures is a signatory to the DGA’s labour agreements — meaning that the studio agrees not to hire non-union directors — Rodriguez’s resignation appeared to take him out of the director’s chair for the John Carter project. Paramount hoped not. “We are in discussions with Mr Rodriguez and are trying to come up with a solution,” Paramount executive Rob Friedman told Variety, while Elizabeth Avellan stated that, “As of today, we are not dropping out. We are still very much making that movie.” A few days later, Rodriguez told Entertainment Weekly that he would not need to rejoin the DGA in order to make the John Carter film because he was assigned to it before he left the union. By May, however, Rodriguez was officially off the project, and the producers had begun talks with another digital film pioneer: Kerry Conran, whose ground-breaking alternate-reality science fiction film Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow had been filmed almost entirely against a blue screen, using the same high definition digital film process as Sin City.

“We’re moving full steam ahead,” Conran told website Rope of Silicon during a pre-release publicity tour for World of Tomorrow in September 2004, adding that a new script was in the works. “Hopefully in the next couple of months we’ll start to move. I think we’ll have a little more resources available this time out,” he added, referring to the modestly-budgeted World of Tomorrow, which Paramount had picked up, finished and distributed. On the question of whether or not the film would be entirely digital, he added: “I think there are certain types of images and effects that the computer isn’t suited for, and you want to use whatever the best approach is for whatever the thing you’re trying to create [is]. So I wouldn’t say that we would want to do it remotely like we did World of Tomorrow, but absolutely we would use some of the techniques.”

In December 2004, Conran visited the offices of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc. in Tarzana, California, to meet with the author’s grandson, Danton Burroughs, and pore over the vast collection of books, comic books, toys, games, merchandise and memorabilia spawned by the John Carter stories. Like most directors newly assigned to a project, Conran brought in his own screenwriter, in this case Ehren Kruger, who scripted Arlington Road and the hit remake of The Ring. “I’m in the writing process for John Carter of Mars, working with director Kerry Conran,” the writer told Now Playing magazine. “We’re pretty [well] along with the script. It’s a faithful adaptation to the novels, but the novels were written in the teens and twenties, so there’s some degree of modernization just to the tone of them. But in terms of the story, we are trying to be as faithful as we can because those novels inspired a lot of science fiction and fantasy that came later in the century.”

Development continued throughout most of 2005, with various conceptual artists being signed to the project, under the supervision of production illustrator and colour stylist Stephanie D. Lostimolo, whose responsibilities included “manag[ing] organization of the art department and all artwork, creat[ing] character sketches and digital painting for the concept phase.” Locations were also being scouted, the strong likelihood being that John Carter of Mars would be filmed in Australia, where the landscape could easily double for the planet Mars, as it had in Red Planet. By September, however, rumours that Kerry Conran had left the project were confirmed. Mike Carambat, webmaster of the unofficial John Carter of Mars fansite, spoke for many John Carter fans when he mourned Conran’s departure. “Personally, I really wanted to see Conran do this film,” he wrote. “He is a master of the early sci-fi pastiche and would have brought a unique visual flair to the project. He will be missed greatly. I can only hope the next director has as much creative vision and attention to detail.”

Carambat and other John Carter fans didn’t have to wait long to find out who had inherited the director’s chair. On 5 October 2005, Variety announced that Jon Favreau, director of the special-effects-heavy family films Elf and Zathura, was attached. Favreau became involved after rounding off a meeting with Paramount executive Brad Weston by asking him about the status of the John Carter project. Upon learning that it was available, and that the underlying rights to the eleven books were about to come up for renewal, Favreau refreshed his knowledge of the source material, and went in to pitch his idea for the film. “The basic take was: Stay true to the books. Keep it intimate. Keep it emotionally true,” he told Ain’t It Cool’s Quint. “Don’t try to turn this into something it isn’t.” Favreau’s take, in addition to what Paramount knew about Zathura and the success of Elf, gave them the confidence to take the leap. “They talked to the [Burroughs] Estate and the Estate then offered to extend the rights based on my involvement in the piece. That was very flattering to me. As a result, I feel that I’m indebted, in a way, to the Estate. I want to stay very true to what Burroughs would have done and I know that Burroughs had foregone a lot of opportunities to make this into a movie because it did not maintain the spirit of the books. So, without being precious and without feeling confined by the plot of it, I definitely want to be true to the spirit of the story.”

“Signing Jon on has been further proof of just how much Paramount values the John Carter property,” producer Harry Knowles wrote on his website, Ain’t It Cool News. “Jon’s first order of business is to bring on a screenwriter to bring the script back closer to Burroughs. He loves that novel. At this stage, Jon is securing the effects and design team that we’ve had through Kerry [Conran]’s tenure on the project and [they’ll] just continue to chip away at the awesome mountain of pre-production that will make this film amongst the finest science fiction/fantasy films of all time.”

Speaking with Empire magazine during a publicity tour for Zathura, Favreau revealed his own take on the classic story. “It’s about a civil war veteran — a cavalry captain — who finds himself transported to Mars and finds himself in the nexus of all these warring tribes on this dying planet with diminishing resources. He also finds himself with what I guess you would call ‘super powers’. At the time it was written, we didn’t understand anything about going to planets with lower gravity and so the way it was expressed was that he had superhuman strength and leaping abilities. So he’s the guy who finds himself at the end of a war that was pretty meaningless, basically, and wasteful on Earth, and ends up showing up on this planet as a super warrior who can actually make a difference.” Pointing out that the story had influenced a great deal of science fiction and fantasy, including Star Wars and the Superman stories, Favreau noted the film’s long development. “This thing has gone through dozens of incarnations, and because of how expansive it is and the fact that there’s only one human character and most of the other characters are fifteen feet tall green Martians, there has never been the technology available to bring it to the screen. But now with the technology that exists I’m pretty confident that we [can] come up with something really cool.” As of January 2006, Favreau explained that a new script and conceptual sketches were being worked on, and that a decision on whether to move forward would be made by the spring. “It’s pretty big,” he added. “Theoretically it could spin out into a fully fledged franchise, which is, I think, the ‘holy grail’ for movie studios right now.”

Favreau’s involvement brought about a great many changes to the project. For one thing, both Rodriguez and Conran were digital filmmakers, whereas Favreau had opted to film most of Zathura using practical effects as much as possible. Although computer generated imagery played its part in both Elf and Zathura, Favreau’s preference was to use it only where ‘in camera’ effects were impossible, or impractical. Secondly, as an actor-director, Favreau was interested in aspects of Carter’s character that may have escaped the interest of other directors. “Most people would approach this as an epic,” he told Ain’t It Cool’s Quint. “I would approach it as a very personal story… It may satisfy purists to use every page of the book, but my first instinct is to just make it about John Carter.” In discussing the film with the studio and other potential collaborators on the project, Favreau likened his approach to the first Planet of the Apes movie, in which an astronaut played by Charlton Heston crash lands on an Earth-like planet where man is ruled by intelligent apes. “It didn’t bend itself out of shape trying to explain the technology behind it,” he explained. “They really made it a personal journey about somebody in a strange land learning about a strange culture in a strange society and eventually getting to a point where he understands it and could communicate with them.”

For Favreau, Planet of the Apes also served as a useful reference for how those fifteen feet tall green Martians, the Tharks, might be rendered on screen. “Even though the make-up was sort of restrictive of the movement of the faces and I wouldn’t want to go completely down that route, I did feel that you were able to differentiate the apes. You knew it was Roddy McDowall in there and it was a wonderful performance and there was emotion involved. What I would like to do is find a way to base it around performers so that I could actually cast people as Tharks and not just their voices to be behind CG puppets,” he explained. “That being said, I have to see what the state-of-the-art CG does right now, but my sense is that it’s a mixture of practical with some sort of CG augmentation to help sell how they’re different from people. I don’t want to just put big shoes on them and rubber arms.”

Another important change Favreau hoped to make was to reject the idea of making John Carter a character from the twentieth or twenty-first century, and return him to his Civil War roots. “If you really did change him to someone coming back from the Middle East it doesn’t tell the complete story. First of all, he couldn’t be a horseman and he couldn’t be a swordsman… And I also think that being an officer in an army that no longer exists really speaks to his character and what makes him who he is. I think to sacrifice that you would lose aspects of the character that you don’t even notice in a development meeting, but ultimately when you see the movie and write the script it would undermine the film.”

Favreau set out to find a new writer who would foster a more traditional take on the material, closer to the spirit of the books. “I don’t know how much of what [Ehren Kruger] wrote were choices that were forced upon [him] or how much came from him,” he noted. “I know that the drafts didn’t really speak to me, in a sense of what I thought was appealing about the books.” Knowing that his strengths lay in the characters and dialogue, Favreau hoped to find a screenwriter who could nail the structure. “What I need is somebody who could help break the back of this piece structurally, so you’re not forced to make tough decisions about what can stay and can go,” he said. “I think there are set pieces that we can build around, but there are problems to be solved logistically about the language, technically about the physiology of the aliens and the alien creatures.” In a bid to make a project their own, many filmmakers coming in to an existing project not only reject existing drafts of the script, but also any conceptual art which has been created prior to their involvement. Favreau, however, did not intend to follow this course of action. “I’ve been looking over all the stuff that the other filmmakers before me, even pre-Conran and Rodriguez, have been doing,” he said. “I think that people have really cared about this and are passionate about it and I welcome anything that anybody’s done right before me. I’m pretty egoless about this thing. The best idea wins. Whatever makes the movie the best it can be.”

Favreau admitted to being daunted by the long development process of the film, likening himself to Jake Gittes in Chinatown as he discovered aspects of the film’s ninety-year journey to the screen. “It’s very overwhelming to think of all these talented people who have been involved with this thing and haven’t been able to crack this nut,” he said. “[George] Lucas was interested in the material before he did Star Wars… and, you know, there’s [John] Boorman, and the list goes on and on of people who really saw the potential in this thing. It’s a bit intimidating in a way, but it also makes me feel like I’m on to something and this is a worthy piece of material to spend the years that I would have to, not just to ensure that one movie would come out good, but that I’m true enough to the material on the first movie that it would lend itself to extending it into a whole franchise.” One thing that did not concern Favreau was the fact that so much science fiction, from Star Wars to Flash Gordon, has drawn so much from Burroughs. “I’m not worried about… trying to reinvent it because it’s too similar to all the movies that have picked the bones of this material for the last, you know, close to a hundred years,” he said. “But I think the fact that it’s been around since then gives you the freedom to go right after it and not be afraid of being similar in certain ways to other things that have subsequently come. I’m going to fly right at it. I’m not gonna be scared of it. You know, you’re dealing with religious issues, you’re dealing with a lot of social commentary. Burroughs had a very strong opinion about religion and about different issues of his time, but ultimately I think the books are very spiritually correct. What Carter represents and what the different cultures represent, it’s a real cautionary tale of where we’re heading in our future and I don’t want to lose that. If you’re going to make a movie of this scope, it has to have a social relevance that is not overtly obvious, but people, as they’re enjoying and being entertained by the movie, under the radar a message comes through. The ‘aspirin in the applesauce’ as they say, and that’s really what’s appealing about this to me.”

Mark Fergus, an Academy Award nominee for Children of Men, was Favreau’s favoured screenwriter, commissioned to adapt the first three books in Burroughs’ series. He had never read the books before, he told the website FilmStew, “which was great because it made it fresh material. I was like, ‘Wow, everyone has pillaged these books over the years for sci-fi stories and movies.’ What we really had to do is focus it to just be a mythical fairy tale,” he added. “It could be a four-hour movie if you wanted it to be. But it’s quite a simple story when you strip away the hundreds of side characters and layers and all of that. When we showed them we knew how to travel through this material and find that story, I think that’s really what made them want to get us involved. I think we nailed that.”

In a message posted to Ain’t It Cool News in April 2006, Harry Knowles confirmed that a new script, “the best one yet,” had been delivered. A week later, Favreau set up a John Carter of Mars forum on his myspace.com page, allowing him to respond directly to fans. “The script and artwork have both been well received and we are awaiting a round of script notes and a budget. When these are complete we will make our final submission to see if [Paramount] has an interest in moving forward with the movie.” Asked about his proposed depiction of the Tharks, he wrote: “The artwork I’ve been supervising keeps them at the book’s dimensions of fifteen feet male/eight feet female for the first time, as far as I can tell, in the film’s development,” noting that earlier versions had attempted to make the creatures human in scale. Later the same month, Favreau posted an update on the film’s gestation. “The project is slowly working its way up the Paramount ladder. For the first time, the project has some fans at the studio. I have been working on it since late ’05 and have foregone many directing offers in hopes that this might be my next movie. The plan was originally to have an answer by the end of February ’06,” he added. “Then March. Then April. Half a year has gone by and I still have no solid commitment.” Nevertheless, he said, the studio continued to be supportive, “but this is not some small project that they can make without weighing out many things.” Among them, Favreau mentioned a concern that, with Paramount having greenlit J. J. Abrams’ Star Trek for a 2008 release, there might not be room for another big-budget science fiction film on Paramount’s slate for that year. And yet, he said, “Regardless of when or how, I am committed to getting it made. The script is there, I know how to execute it, and I am passionate about making it.”

Favreau’s concerns were justified. Only four days after this posting, the director confirmed that Paramount had put John Carter of Mars “back on the woodpile,” blaming Star Trek and other “similar” stuff in the studio’s pipeline. “I am trying to help position the film to get made and remain committed to seeing it through,” he added. By June, however, Favreau had signed on to direct Marvel Comics’ Iron Man movie for Paramount — co-scripted by Mark Fergus — although he tried to remain optimistic about John Carter of Mars. “I’m hoping that if Iron Man goes well, the studio may be a bit more enthusiastic about a project that I am passionate about.” Favreau was realistic, however. “I think that there isn’t a tremendous amount of enthusiasm for John Carter of Mars over at Paramount, regardless,” he admitted. “If there was, they would’ve made it. The script and art were great… [but] John Carter of Mars has always been a tough sell. I really want to break the curse.”

It was not to be. In August 2006, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc. confirmed that Paramount Pictures had not exercised their option to renew the underlying rights to the stories. “Jim Jacks, Sean Daniel and I — along with Jon Favreau — were heartbroken when Paramount didn’t renew the rights,” Harry Knowles told Ain’t It Cool News. “But that happens. Ultimately I’m just proud to be a part of the long history of people that tried to bring this great story to the screen. We came the closest.”

Throughout 2006, rumours persisted that The Walt Disney Studios would be the studio to take on the project, possibly as a vehicle for director Robert Zemeckis, an avowed Burroughs fan whose preferred brand of motion capture animation suggested that John Carter of Mars might be made, like Beowulf (2007), in 3D. In January 2007, however, The Hollywood Reporter revealed that Disney was in final negotiations to acquire the rights not for Zemeckis’ new production outfit, but for Pixar, the Disney-distributed CG animation studio behind such films as Toy Story, Finding Nemo and The Incredibles. The following month, studio chairman Dick Cook let slip that Disney was trying to figure out whether John Carter of Mars would be live action, animation, or a combination of both. Over the next few months, Pixar personnel would only admit that the company was moving forward with the project, and that audiences could expect something edgier than Pixar’s usual PG-rated fare. Disney added fuel to the fire in August 2007 by registering several variants of johncarterofmarsthemovie as domain names, yet neither studio would be drawn on the details of the deal.

In October 2007, ERBzine (the ‘Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute and Weekly Webzine Site’) reported that the Pixar creative team — namely vice president Jim Morris, director Andrew Stanton (WALL•E) and screenwriter Mark Andrews (Ratatouille) — had spent a morning exploring the massive archives in the offices of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc. with its representatives Danton Burroughs, Sandra Galfas and Jim Sullos. “All six members of the meeting expressed a deep commitment to the project, acknowledging that they had been inspired by Burroughs’ creations from a very early age. This is evidenced in the excitement held for the John Carter property and the plans for a film trilogy faithful to the Burroughs books.” By this time, Pixar had announced its first foray into live-action filmmaking, 1906, a film about that year’s San Francisco earthquake, to be directed by Brad Bird (The Incredibles), while Disney had announced its entire slate of animated titles for the next four years. This suggested that, despite the presence of Pixar animation veterans Stanton and Andrews at the helm, the John Carter of Mars trilogy would be filmed in live action, rather than the studio’s customary CG animation.

By March 2008, it was rumoured that Andrews had completed a first draft of the screenplay for the first film in the proposed trilogy, and that Stanton and former Lucasfilm Digital producer Jim Morris would begin mapping out a battle plan for the project as soon as Stanton’s production and promotional duties on WALL•E were completed. For better or worse, John Carter would arrive in cinemas in 2012, 100 years after the publication of the very first John Carter story.

The above first appeared in The Greatest Sci-Fi Movies Never Made by David Hughes. Used by permission.